The purpose of this post is not to debate the pros and cons of GMOs, nor to defend the use of GM crops at all costs. Instead, I want to address the flawed way in which the debate around GM crops is often approached.

One of the main concerns about Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) is their perceived lack of naturalness, as these organisms would not exist without human intervention. Genetic manipulation of crops aims to customize the DNA of plants to give them interesting traits such as pest resistance, increased yield, or additional nutrients. The legitimacy of this technology is often questioned because the GM species would not exist without human intervention. To address this topic, I will compare GM technology to other processes that have been widely accepted without their legitimacy ever being questioned.

Domestic crops are wild species that have been genetically reshaped

Most fruits and vegetables we eat today are the result of years, decades, or even centuries of human breeding. Tomatoes, carrots, eggplants … none of these exist in their current form without human intervention. Over generations, plants with desirable traits were selected and bred, gradually transforming the original wild species. In fact, many domesticated crops as we know them today wouldn’t exist at all without this process.

Long and beta-carotene rich carrots, fleshy aubergines, and strong ears of corn are not “natural”; they are purely the creations of humans through genetics. This means that while GM technology may be seen as less “natural” than traditional breeding methods, it is important to recognize that traditional breeding methods have also led to significant genetic modifications.

The debate on GM crops should not solely focus on their lack of naturalness, but rather on their potential benefits and risks. By acknowledging the ways in which humans have already modified plants through traditional breeding, we can have a more nuanced discussion about the legitimacy of GM technology.

Source : Business insider (see end of the video 1:49)

One striking example is the domestication of wild mustard (scientifically known as Brassica oleracea). This ancestral species has given rise to many of the species we now eat on a daily basis. By selecting plants with desirable traits such as over-developed buds, large leaves, and big stems, humans have created entirely new species such as cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, and broccoli.

Inducing mutations for an artificial evolution

In the latter half of the 20th century, a new method for creating crop species emerged: inducing random mutations using radiation (X-rays or Gamma rays) and chemicals (such as Ethyl methanesulfonate) on a large population of seeds. Each seed was then sown, and those that truned into plants that exhibited desirable traits were selected, resulting in the creation of brand new species such as the “Lysgolden Goldenir” apple, which is a “Golden Delicious” apple without the roughness of its skin. It’s clear that these fruit and vegetable species exist because we induced mutations using very harsh treatments. It doesn’t fit the definition of “natural plants” that most people have in mind. Although these species are genetically modified, they are not considered as GM crops since the legal definition of genetic modification involves “introducing DNA into an organism”.

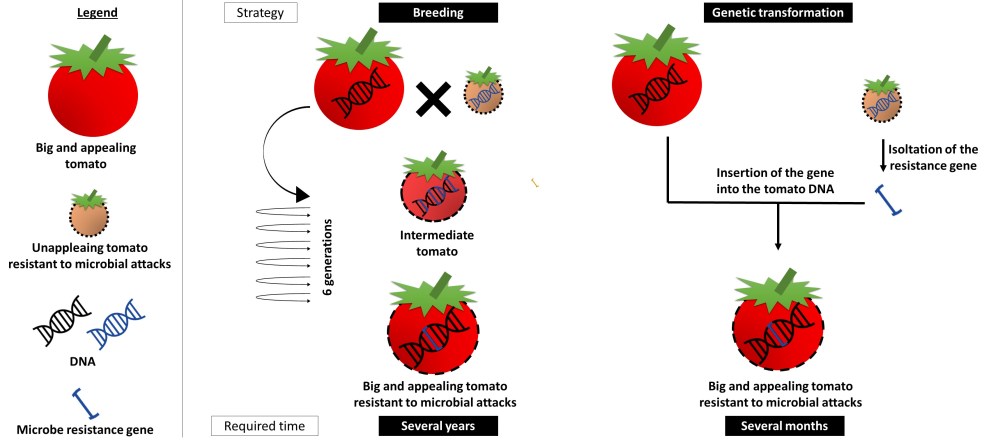

Genetic modification should be seen as just one tool in the laboratory, among many others, with the same goal of improving crops, just as crop breeding has done. The difference is that genetic modifications are much quicker than classical breeding. For instance, consider a tomato plant that produces tasty fruit but is susceptible to fungal attacks, and another one with unpalatable fruit but can resist fungal attacks thanks to a specific gene. You can either crossbreed these two species and obtain, after several generations, plants with the desired traits or directly transfer the gene responsible for resistance into the plant that produces tasty fruit. From a genetic standpoint, both methods result in the same product, but one is fully accepted while the other is heavily rejected by the general population.

So what’s the problem? I believe it stems from the different definitions of genetic modification given by politicians and scientists. Legally, introducing new genes is not considered the same as inducing mutations or deleting genes, which is absurd because they are all genetic modifications, biologically speaking.

Up until now, we’ve been discussing introducing genes from one plant species to another, but GM technology also allows us to introduce genes from different species, or even kingdoms, such as a bacterial gene into plants. It’s tempting to say that this is quite “unnatural,” isn’t it?

Sweet potatos, natural GMOs

To insert a gene into the DNA of plants, biologists use a very special bacterium called “Agrobacterium tumefaciens.” In nature, these bacteria infect plant roots and have the remarkable ability to inject several of their genes into plant DNA, forcing the plants to produce chemical compounds called opines. Opines serve as growth factors for the bacteria, which literally hijack plant cells for their own benefit. Scientists use this property of Agrobacteria to insert DNA into target plants, but they replace the bacterial opine-biosynthesis genes with “gene(s)-of-interest,” allowing any genes to be inserted into plants. This is one of the possible approaches to create genetically modified (GM) plants.

In 2015, a striking discovery from a research lab in Peru changed the way we view GMOs (scientific article published in PNAS here). Deep sequencing analyses revealed that sweet potatoes contain Agrobacterium genes, which are still active. All 200 analyzed sweet potato species, including those commonly cultivated, have been transformed by Agrobacteria long ago. Sweet potatoes are, in fact, natural GMOs. Even more striking, since all cultivated sweet potato species contain these bacterial genes, it seems that we unconsciously selected sweet potatoes with these foreign genes because they provide desirable agricultural or gustatory traits.

In a nutshell, genetic modifications have occurred in nature, and we have benefited from them. Rejecting GM technology while accepting plant breeding methods could be compared to being shocked by introducing genes from bonobos into humans with laboratory genetics, but being totally fine with making hybrids by mating. One must keep in mind that genetic modification is just another molecular tool in biology, like 3D printing in architecture, design, and medicine. GM crops can be used to flood fields with pesticides and other toxic chemicals, but they can also save crop species from disappearing due to devastating pathogens (such as bananas or coffee) or when these crops are difficult to breed. Ultimately, technologies are neither inherently good nor bad; it depends on the purposes we use them for.