With this article, I have been awarded the 1st prize for “Best Qualitative Research Project” as part of the 12-week long Pandemic Preparedness 2024/2025 course by BlueDot Impact.

Estimated reflective reading time: ~40 minutes

Abstract

Pandemics can have devastating effects on society, as we’ve witnessed most recently with the COVID-19 crisis. And according to scientists, the question is not if there will be another pandemic, but when. One of our best tools for fighting pandemics are vaccines. To prepare for potential upcoming disease outbreaks, enormous efforts are focused on accelerating the development, validation, and production of vaccines, so the population can get protected as quickly as possible. Yet, one crucial aspect is still largely overlooked: the vaccination strategy itself.

In the event of a pandemic, our instinct is to vaccinate the most vulnerable people first, as soon as a vaccine becomes available. But, what if I told you that vaccinating just a small, specific group of people could stop the propagation of a disease more effectively … and save more lives?

In this article, I dive deeper into a counter-intuitive vaccination strategy rooted in network science, exploring the mechanisms, challenges, and ethical questions it raises – questions that are crucial to consider before the next pandemic strikes. Who is this article for? Policymakers, who need to think through vaccination strategies now, but also the general public, so everyone, because this topic addresses choices that affect all of society.

Could this alternative vaccination strategy reshape how we fight pandemics? Let’s find out together.

Pandemics have long been among humanity’s most devastating challenges, claiming hundreds of millions of lives throughout history [1]. From the Black Death in the 14th century to the 1918 influenza pandemic and, more recently, the COVID-19 crisis, pandemic caused by infectious diseases have repeatedly overwhelmed healthcare systems, reshaped societies, and disrupted economies. In today’s interconnected world, this challenge is even more acute, as pathogens can spread at unprecedented speeds, turning a local epidemic into a global pandemic in a matter of weeks. In addition, advances in synthetic biology and genetic engineering have enabled the potential creation of human-made pathogens, increasing the threat of bioterrorism and its catastrophic consequences [2]. Together, these risks make pandemic preparedness one of the most urgent issues of our time [3].

Vaccines to combat pandemics

Despite the threat of pandemics, we are far from helpless: advances in science, technology, and society have equipped us with tools to significantly reduce the impact of infectious disease outbreaks. These include preventive measures such as public health interventions (e.g., quarantines, travel restrictions, and social distancing) and the use of personal protective equipment like masks; diagnostic tools for early detection, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR), loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) [4], antigen tests, and more recently CRISPR-based tests [5]; and therapeutics to treat patients, reduce disease severity, and lower mortality rates. But the most powerful weapon to combat infectious disease outbreaks may very well be vaccines.

Vaccines prime the immune system to fight specific pathogens, often reducing the risk of infection, symptoms, and transmission, and in some cases, preventing infection entirely. For diseases transmitted from person to person, vaccines have a dual action: not only do they protect the individuals who receive them, but they also protect the broader population. Once most people are vaccinated, transmission chains are interrupted, and the disease’s ability to spread within the population diminishes significantly, until it potentially vanishes. This phenomenon, known as herd immunity, occurs when enough individuals are immune to a disease, either through vaccination or recovery from a previous infection [6]. The threshold for herd immunity varies by disease, depending on factors such as how contagious the pathogen is. For instance, herd immunity for measles, a highly contagious disease, requires approximately 95% of the population to be vaccinated, whereas it requires 80% for polio, a disease with lower transmissibility. Achieving herd immunity is crucial to protect those who cannot be vaccinated, such as those with compromised immune systems, pregnant women, or people with allergies to vaccine components, making vaccination campaigns a cornerstone of pandemic responses [6].

Accelerating pandemic vaccination efforts

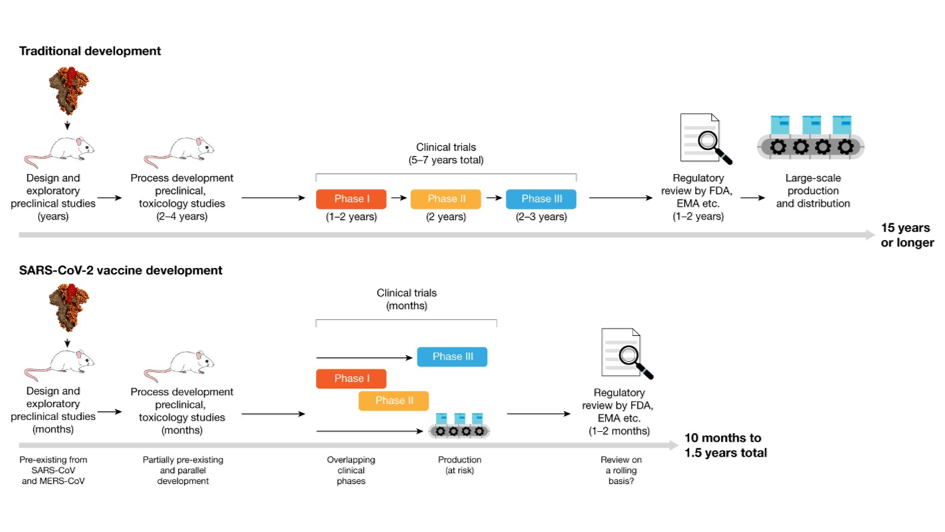

Despite the immense progress that vaccines have brought to managing some infectious diseases, their impact during pandemics is constrained by the time required to implement them. When an outbreak begins, a series of time-consuming steps must be completed before the vaccination protects the population via herd immunity (Figure 1) [7]. First, scientists must identify the pathogen causing the epidemic. Next comes the complex process of developing vaccines candidates, followed by rigorous clinical trials to ensure their efficacy and safety. Then, validated vaccines must be mass-produced and finally administered to the population. This multi-phase process is lengthy, and a development time of 15 years is common [8].

Figure 1. Traditional and accelerated vaccine-development pipelines. Traditional vaccine development can take 15 years or more, whereas the accelerated timeline for vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 took less than a year thanks to very fast design and pre-clinical development, overlapping clinical trials and accelerated review by regulatory agencies. Adapted from [8].

During the COVID-19 crisis, the first vaccine shot was administered less than a year after the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus was identified in early January 2020 [9]. This achievement was nothing short of remarkable. However, even this unprecedented speed left significant gaps. By the time the vaccine became available, millions of infections, hospitalizations, and deaths had occurred worldwide. This highlights the urgency of reducing the time between pathogen detection and population-wide vaccination.

Technological advances provide hope for addressing some of these delays. For example, initiatives like the “100 Days Mission” aim to deliver vaccines in the future within 100 days after identifying a new pathogen presenting an epidemic risk [10]. Innovative vaccine technologies such as mRNA platforms and adaptive platform trials aim to shorten development and validation processes [11, 12]. However, a significant bottleneck remains largely overlooked: the time needed to vaccinate the population and achieve herd immunity.

In the event of a pandemic, every day gained can make a difference, as disease propagation leads to surging cases and overwhelmed healthcare systems. Reducing the time needed to vaccinate the population is, therefore, also a critical goal in pandemic preparedness. While technological innovation and advances can speed up vaccine development and production, improving how the vaccination of the population is carried out can maximize its impact and save a precious time, and, by extension, lives.

For COVID-19, while the world was just ticking over and vaccines were expected to solve the crisis (which they eventually did not, although they did help [13]), it took months to vaccinate a significant portion of the global population. In France, it took 12 months for 77.2% of the population to get a full vaccination against COVID-19 [14], while it took Germany 11 months to reach 68.3% [15]. Factors such as limited vaccine supply, high global demand, and vaccine hesitancy contributed to these delays. If the vaccination campaign had progressed faster, many infections, hospitalizations, and deaths could have been prevented. This underscores the critical importance of accelerating vaccination efforts to better prepare for future pandemics and reduce their impact on global health.

Vaccination strategy: age before beauty

In many countries, vaccination strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic prioritized certain groups before expanding eligibility to the general population [16, 17]. The first priority group, known as “high-risk group”, included the elderly and individuals with pre-existing conditions, as they faced the highest risk of severe outcomes. Vaccination for this group was often phased, with the age threshold for eligibility gradually lowered over time. A second group, ” healthcare workers,” concerned individuals working in hospitals, elderly care homes, and care centers, due to their close contact with high-risk individuals [18]. In many countries (such as the US, the UK, France, Germany, Spain, Italy, Japan, Argentina, and Australia, to name a few), the vaccination campaign initially started with the first and second priority groups simultaneously.

Another group received varying levels of prioritization: teachers, school staff, and childcare workers [19]. Only 47 countries worldwide placed this group in top priority. Countries like China, Russia, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Morocco prioritized them highly, while others, such as the U.S. and Germany, included them in priority groups but after “high-risk” individuals and “healthcare workers” [20].

Subsequently, vaccination was opened to the general population, allowing anyone eligible to get vaccinated on a “first-come, first-served” basis, although children, pregnant women, and individuals with allergies to vaccine components were often excluded from the vaccination campaign. For example, in France, adults who were neither high-risk nor healthcare workers became eligible for vaccination on May 31st 2021 [21], and in Germany, on June 7th 2021 [22], which is in both cases five months after the vaccination campaigns began.

This approach is sensible, as it prioritized protecting the most vulnerable and some of the most exposed people, while ensured equal access to vaccination for everyone afterwards. However, it fails to fully exploit the dynamics of disease transmission. Based on principles of network science, there is an alternative strategy that has been largely overlooked, offering a potentially more efficient approach to vaccination in the event of a pandemic.

What is network science?

To understand the principles of this alternative vaccination strategy, it is important to first explore the basics of network science, an academic field that examines interactions between components within a system [25]. It focuses on distinct elements or actors, represented as nodes, and the connections between them, represented as links or edges. Networks are ubiquitous across various disciplines, including telecommunications, infrastructures, informatics, biology, and social sciences. Network science explores various systems, such as how cities are interconnected, how routers form the internet, how society is structured through social interactions, how proteins interact within a cell, or how species dynamics shape ecosystems, to name but a few (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A few examples of networks.

a. Simplified fictive social network representing people (nodes) connected to each other by friendships (links).

b. Food web network illustrating the prey-predator relationships (arrows) between species (nodes). From [23].

c. Protein-protein interaction network in baker’s yeast represented by proteins (nodes) connected to the other proteins it physically interacts with (links). From [24]

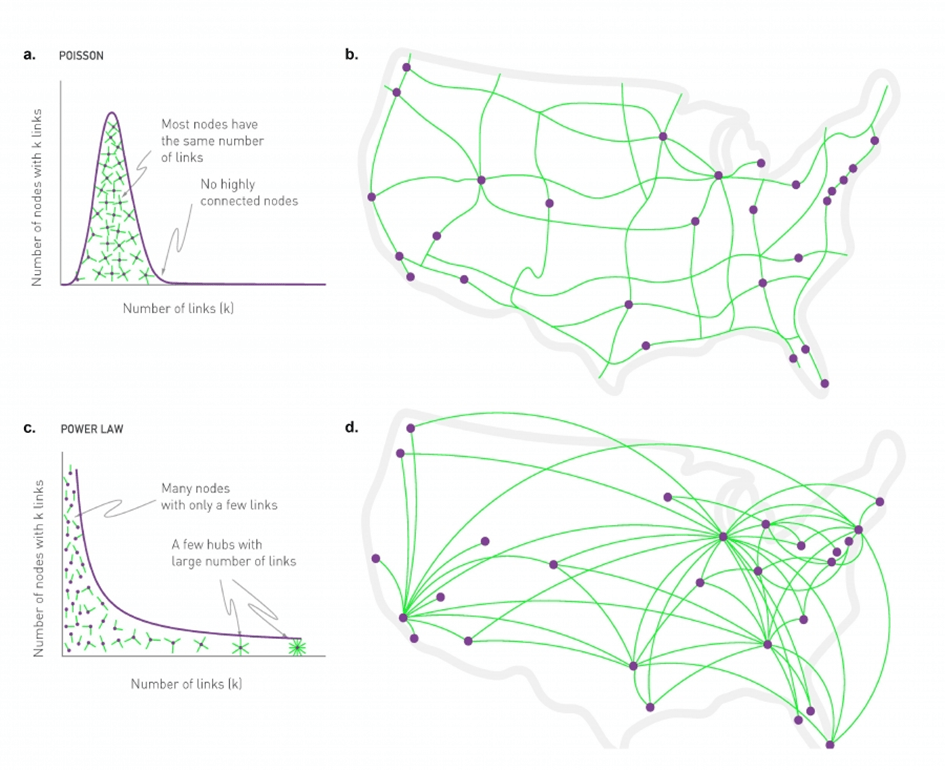

Some networks are random, meaning that most nodes have about the same number of connections (Figure 3a). The number of connections of the nodes follows a predictable pattern called a Poisson distribution, implying that few nodes have significantly more or fewer connections than the average. Fall in that category networks like the road network in the US (Figure 3b)[25].

Yet, many real-world networks are not random. Instead, they are composed of most nodes with very few connections and a small number of nodes with many connections. The number of connections of the nodes follows a predictable pattern called Power Law. The highly connected nodes are called “hubs”, and these networks are referred to as “scale-free” because the pattern of connections looks similar whether you’re examining a small or large portion of the network (Figure 3c). A classic example of a scale-free network is the airports network in the US, where a few major airports are extensively connected (e.g. Chicago, Atlanta, Los Angeles), while most other airports have limited connections (Figure 3d)[25].

Figure 3. Random and scale-free networks.

a. Random networks. Nodes have a connectivity that follows a Poisson distribution. Most nodes have the same number of connections, and no node is highly connected.

b. US roads form a random network.

c. Scale-free networks. Nodes have a connectivity that follows a power law distribution. Most nodes have only a few connections, but a few ones are highly connected. Those nodes are the hubs.

d. US airports form a scale-free network.

Figure from [25]. Author: Albert-László Barabási; Design & Data Visualization: Max Tillich, Kim Albrecht, Mauro Martino, Márton Pósfai and Gabriele Musella).

Similarly, the internet, a vast network of interconnected routers, is composed of a few highly connected nodes, which are disproportionately connected compared to most less-connected nodes [26]. Social networks (such as “who knows who,” “who is friends with whom,” or “who is connected to whom on a social media”) also follow this pattern, with a few highly connected individuals being far more popular than most others [27]. Biological systems like ecosystems, metabolisms or protein-protein interactions often exhibit scale-free properties as well.

Since most nodes in scale-free networks are poorly connected, random removal of nodes typically has little effect on the network’s cohesion. In other words, scale-free networks are highly robust against random attacks. In fact, scale-free networks are so robust that often, the gradual removal of nodes does not disrupt the network until one of the very last nodes (Figure 4 top, from [25]). The threshold at which a network collapses depends on its specific structure. On the other hand, scale-free networks are very vulnerable to targeted attacks (Figure 4 bottom, from [25]). Since hubs are essential for the network’s cohesion, removing a few hubs can significantly damage or even destroy the network. Targeted attacks on hubs are often described as the Achilles’ heel of scale-free networks [28]. For example, the collapse of the internet network occurs after the random removal of 92% of routers, but only after removing the 16% most connected ones. Similarly, these thresholds are 88% and 16%, respectively, for the yeast protein-interaction network; and 92% and an astonishingly low 4% for an e-mail network, where nodes represent e-mail addresses and links represent e-mails sent between addresses [29].

Figure 4. Scale-free networks are robust to random attacks but vulnerable to targeted attacks. Video from [25]. Visualization by Dashun Wang. https://networksciencebook.com/chapter/8#attack-tolerance

Top. The network starts breaking apart only from the 35th random node removal, which is 70% of the nodes, illustrating the robustness of scale-free networks to random attacks.

Bottom. The network loses its integrity from the removal of the 7 most connected nodes, which is 14% of the nodes, illustrating the vulnerability of scale-free networks to targeted attacks on hubs.

Super-spreaders: the hubs of infectious disease networks

The spread of infectious diseases with person-to-person transmissions can also be represented using networks, where individuals are nodes and transmissions are shown as directed links. Since many of the infectious diseases that caused pandemics are transmitted through proximity or contact, the networks that model their spread are essentially social networks [30]. This is particularly true for airborne diseases like influenza, SARS, H1N1, and COVID-19, as well as sexually transmitted diseases like AIDS.

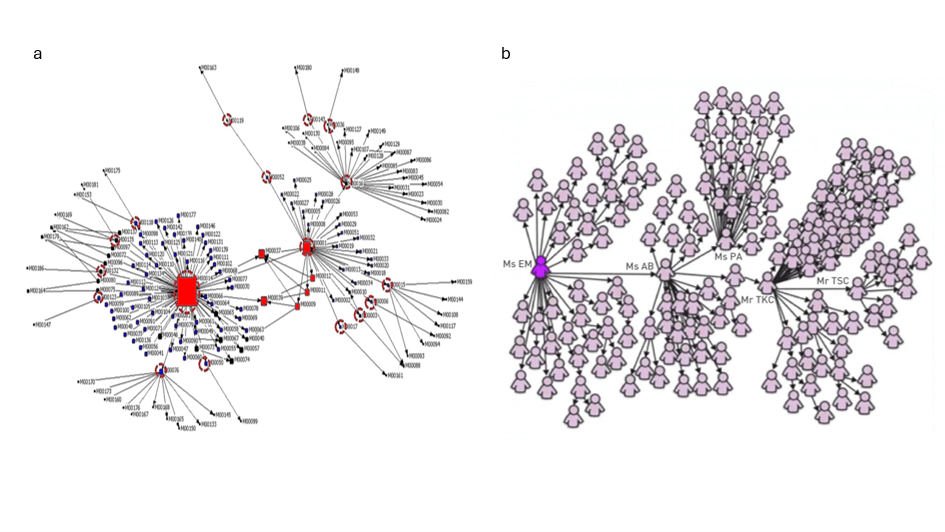

These networks often follow a scale-free pattern, as confirmed by epidemiological studies [31, 32, 33], including research on the COVID-19 pandemic [34, 35]. Most individuals transmit the disease to no or few other people. For example, a study conducted in Hong Kong found that 69% of COVID-19 positive individuals did not transmit the virus to anyone else [36]. These individuals may become infected, remain asymptomatic or fall ill, recover, or even succumb to the disease, all without passing it on. On the contrary, a small subset of individuals, known as “super-spreaders”, transmit it to a disproportionately large number of persons [37, 38, 39]. In the field of epidemiology, super-spreaders act as hubs within infectious disease transmission networks (Figure 5).

Studies on the dynamics of infectious disease transmission reveal that 80% of the spread is caused by just 20% of cases [37, 40], with this figure dropping to approximately 10% for COVID-19 [41, 42]. This underscores the significant role of super-spreaders in disease propagation. This phenomenon helps explain some puzzling aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, while isolated cases of COVID-19 were recorded in France as early as December 2019, the virus did not cause a wider outbreak until much later [43]. The reliance on super-spreaders to drive transmission may explain why the disease failed to ignite a global pandemic earlier despite its early emergence in different locations.

Figure 5. Super-spreaders act as hubs in infectious disease transmission networks.

Two examples illustrating the scale-free nature of infectious disease transmission networks. Nodes are individuals and arrows indicate the transmission of the disease to someone else. The networks display a scale-free topology, where most individuals transmit the disease to few persons or no one, while a few individuals transmit it to an outstanding number of people.

a. Personal Contact Patterns in MERS Infection Transmission in South Korea in 2015. From [31]

b. 144 of the 206 SARS patients diagnosed in Singapore in 2003 were traced to a chain of five individuals that included four super-spreaders. From [44].

Leveraging network science for vaccination

Vaccination is a powerful tool for combating infectious disease outbreaks, as it protects not only vaccinated individuals but also indirectly those who remain unvaccinated within a vaccinated population. From the perspective of network science, vaccination effectively breaks transmission chains. Halting an epidemic through vaccination requires disrupting the transmission network’s integrity to the point where it collapses into small, isolated fragments of the original network. At this stage, the outbreak is effectively contained and stops spreading further. In epidemiology, this critical threshold is referred to as herd immunity [6]. When considering the spread of an infectious disease as a network, network science highlights two key insights:

- Random vaccination is not an efficient strategy for quickly containing an outbreak, as most individuals contribute minimally to the spread of the pathogen.

- The most effective way to stop an outbreak is to immunize the hubs.

From a network perspective, vaccinating vulnerable and older individuals is comparable to removing some of the least connected nodes in the disease transmission network, as they are generally less socially active [45, 46]. In addition, voluntary vaccination programs function similarly to random node removal.

On the other hand, immunizing healthcare workers is a more targeted approach; these individuals are highly connected and frequently interact with high-risk populations. Similarly, immunizing teachers is a prudent strategy, as they interact with numerous individuals, especially considering that children were ineligible for vaccines initially in most countries. Research supports the importance of prioritizing high-contact occupational groups to enhance vaccination effectiveness. For instance, vaccination campaigns prioritizing such groups achieved similar infection reductions with half the number of vaccines compared to non-prioritized approaches [47]. However, while vaccinating healthcare workers and teachers is effective, it may not directly target the true super-spreaders.

Network science suggests that targeting specifically super-spreaders would be far more effective in impairing the network, breaking transmission chains, and halting the spread of disease [48]. Modeling suggests that it is possible to protect the entire population by immunizing just 16% of people [49], provided the vaccination prioritizes those with the highest number of connections. This assumes that the pathogen does not evade vaccine coverage, a factor that was partially an issue with SARS-CoV-2 but is not central to the discussion in this article. With a similar vaccination rate, this approach of vaccinating super-spreaders in priority could achieve the target coverage faster than classical vaccination strategies, ultimately saving time, hence reducing the number of infections, and potentially hospitalizations and deaths. Furthermore, by accelerating the timeline, this alternative strategy could have allowed for an earlier relaxation of public health interventions such as quarantines and social distancing measures, thereby mitigating their detrimental impact on the economy and societal well-being.

Can we identify super-spreaders?

The potential of this alternative vaccination strategy raises an important question: who are the super-spreaders? Several factors related to the individual and the pathogen contribute to the phenomenon of super-spreaders [37]. However, these factors are conditioned by one critical feature: the individual’s higher number of social interactions compared to the average person. As a result, behavioral and environmental factors play a more significant role in determining whether someone is going to become a super-spreader. The archetype of super-spreaders is being middle-aged, belonging to a large, multigenerational family, holding a job that involves frequent interactions with strangers, and maintaining an active social life, such as attending large gatherings or engaging with diverse groups [50]. As a matter of fact, these traits contrast sharply with those of individuals prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination: the elderly and medically vulnerable people.

Identifying super-spreaders is critical for controlling outbreaks. While the forementioned traits provide a general idea of who these individuals might be, pinpointing them precisely remains a significant challenge. Doing so requires access to detailed interaction maps tracking people’s contacts over time. Social tracing apps , such as those using location-tracking and phone-data surveillance, gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic and offer a potential tool for identifying individuals with an unusually high number of interactions [51]. These apps leverage the ubiquity of mobile devices to track who was in close proximity to whom and for how long. However, this approach is fraught with limitations.

A key challenge is that super-spreaders are typically identified retrospectively. Yet, to contain an outbreak effectively, it is crucial to predict who they are in advance to be able to immunize them early on. This raises an important question: should we prioritize identifying social hubs during a disease outbreak, when public health measures like social distancing may alter interaction dynamics, or should we identify these hubs during non-pandemic periods, when they are more likely to remain consistent after the relaxation of social distancing measures and/or vaccination? In the latter case, identifying hubs before a pandemic requires analysis during ordinary times, but these individuals might not remain hubs during an outbreak if they adhere to social distancing. In the former case, hubs are identified based on interactions during the early stages of an outbreak, but by the time they are identified, they may have already contributed significantly to transmission.

To address these challenges, data gathered from the COVID-19 pandemic could provide valuable insights. Analysis of past tracing data might help identify individuals with consistent super-spreader behaviors who are likely to act similarly in future pandemics. However, this approach also raises the question of whether super-spreaders are consistently so. In other words, is a person who is a super-spreader during one pandemic likely to be a super-spreader during another caused by a different disease? The answer is far from certain, as biological, environmental and pathogenic-related factors also contribute to making somebody a super-spreader [37].

Since relying on interaction data from previous disease outbreaks or from ordinary times appear to be too approximative, data could be collected during the early phase of an outbreak while vaccines are being developed and the vaccination campaign has not started yet. Even under the optimistic scenario where vaccines can be produced in 100 days in the future [10], this timeframe allows for the recording and analysis of social interaction patterns to identify would-be super-spreaders for targeted vaccination.

Pragmatism versus ethics

Focusing vaccination efforts on super-spreaders offers a pragmatic approach to controlling epidemics. Research suggests that vaccinating super-spreaders could significantly reduce transmission while using fewer resources. For example, if the first doses of COVID-19 vaccines in France and Germany had been prioritized for the 16% most highly connected individuals (i.e. enough to disrupt the transmission network according to modeling) [49], theses hubs could have been vaccinated by April 2021. This achievement would have been possible just a couple of months after the vaccination campaigns began, curbing the outbreak more effectively. Additionally, such an accelerating immunization strategy mitigates risks associated with slow vaccination campaigns, like the emergence of vaccine-escape mutations [52]. Unlike measures like accelerating the vaccines development and production that require technological advancements, prioritizing super-spreaders has the immense advantage of being feasible with no major technological breakthrough, making its implementation easier.

However, this strategy raises significant ethical concerns. Identifying super-spreaders typically requires intrusive data collection, such as tracking social interactions via mobile apps. These methods raise serious concerns about privacy and the potential misuse of personal data. While many apps generate anonymous data, one alternative could be the use of radio frequency identification (RFID) tags for anonymous tracking, which would allow the monitoring of interactions without revealing personal identities [53]. This mitigates some privacy concerns, but it still requires a high level of trust from the public and careful oversight to prevent misuse. Moreover, the complexity of mapping global interaction networks makes identifying super-spreaders an immense logistical challenge.

Ethical dilemmas extend beyond data privacy. Labeling individuals as super-spreaders risks stigmatization and discrimination. This is evidenced by public backlash that happened following a super-spreading event of COVID-19 in South Korean linked to gay venues, which led to a rise in homophobia [54]. Such incidents highlight the potential for targeted strategies to create social divisions. Additionally, prioritizing super-spreaders could inadvertently favor sub-populations, or reversely, put some at a disadvantage.

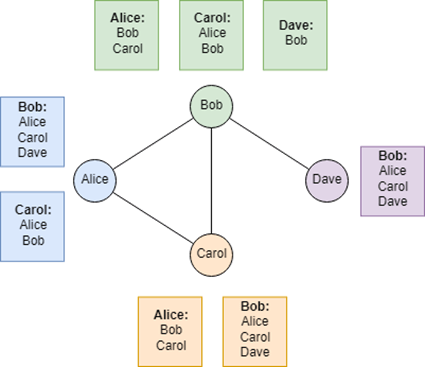

An alternative to identifying super-spreaders avoids many of the forementioned issues exists: acquaintance immunization. This strategy leverages the “friendship paradox,” which tells that an individual’s friends are more socially connected, on average, than the individual themselves (Figure 6) [55, 56]. By asking randomly selected individuals to nominate someone they know, the resulting group of nominees includes more social individuals and, consequently, potential super-spreaders. The vaccination of this nominated group will hence indirectly target hubs without requiring comprehensive global network data. A study suggests that this approach is efficient and could dramatically reduce transmission with fewer vaccines, potentially halting an epidemic by immunizing just 10–20% of the population [57]. The comparision of a control group with a nominated group showed that the nominated group caught the seasonal flu two weeks earlier, highlighting the potential benefits of immunizing this group and the effectiveness of acquaintance-based immunization strategies. Another alternative is even simpler: surveying the population 10 people at a time and vaccinating the person who reports having the most connections.

Figure 6. The friendship paradox. Here is a simplified friendship network. For each person are shown the friends of their friends. Every time, the number of friends is smaller than the average number of friends of their friends. Except for Bob, who is here the hub. From [56].

However, prioritizing super-spreaders (either with direct identification or alternative methods) introduces another capital ethical dilemma: while vaccinating these individuals could be more efficient in controlling the outbreak, it would delay the vaccination of vulnerable groups, such as the elderly or high-risk individuals. This delay could result in avoidable infections and deaths among those who might otherwise have received the vaccine early. The balance between efficiency and protecting the most vulnerable remains a contentious and deeply challenging issue. Is it ethical to vaccinate a highly social 29-year-old who is not respecting social distancing and is likely to easily recover from the disease over an 86-year-old in a nursing home, whose infection could be fatal? This tension between efficiency and equity underscores the challenge of balancing public health priorities with individual rights.

However, vaccination strategies do not have to be binary. Several alternatives for implementing super-spreader targeting are possible. The immunization of super-spreaders could be prioritized in several ways without omitting to prioritize high-risk individuals. For instance, super-spreaders could be immunized from the beginning, alongside vulnerable individuals, rather than focusing on other groups such as teachers or healthcare workers. Alternatively, vulnerable individuals, teachers, and healthcare workers could remain the top priority, while random vaccination could be delayed making super-spreaders an intermediate priority. The strategy should in any case be carefully designed to complement social distancing measures, ensuring that vaccination efforts align with other public health interventions.

Finally, a sine qua non condition for the success of the super-spreader vaccination strategy is that they agree to get vaccinated. However, the high level of vaccine hesitancy in many countries makes it far from certain [58].

Pandemic preparedness with thoughtful debate

While much of the focus on reducing the time needed to protect populations during a pandemic has centered on technological advancements, there are overlooked strategies that require no such breakthroughs. Leveraging network science to adapt vaccination strategies is one such option, offering an approach that could be implemented immediately. By targeting individuals who play a disproportionate role in spreading disease, this method promises to maximize the impact of limited resources and potentially save lives.

However, the efficiency of targeted vaccination strategies comes with ethical trade-offs. Are we willing to compromise data privacy and risk potential discrimination to pinpoint super-spreaders? Moreover, prioritizing certain individuals for vaccination raises difficult moral questions and is reminiscent of the trolley problem: deciding to expose some individuals to a higher risk of fatal outcomes in order to save many others (Figure 7) [59]. The best course of action for the population may conflict with considerations of fairness and individual rights, forcing society to grapple with complex ethical dilemmas. This approach is so controversial that even some network scientists who contributed to the concept of targeting super-spreaders argue that vaccination should remain prioritized for at-risk individuals.

The question of who to vaccinate first in the event of a disease outbreak goes beyond technical considerations, it also raises fundamental societal questions. Preparing for future pandemics requires more than scientific innovation; it demands thoughtful public discourse about the values and priorities that guide our decisions. By starting these conversations and debates now, we can ensure that we have a clear, well-considered vaccination strategy in place for the next pandemic, one that balances pragmatism with ethics. Such preparation could save critical time and lives when the next pandemic arises.

Figure 7. The trolley problem.

Is it acceptable to save a greater number of people by sacrificing a smaller group who might not have been harmed without intervention? Adapted from [59].

To cite this article

Valentin Hammoudi (2025). How network science could revolutionize the pandemic vaccination strategies. Bluedot impact pandemic preparedness course. https://valentinhammoudi.com/2025/01/10/how-network-science-could-revolutionize-pandemic-vaccination-strategies/

References

[1] Saloni Dattani (2023) – “What were the death tolls from pandemics in history?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org.

https://ourworldindata.org/historical-pandemics‘.

[2] Wickiser JK, O’Donovan KJ, Washington M, Humel S, Burpo FJ (2020). Engineered pathogens and unnatural biological weapons: the future threat of synthetic biology. CTC Sentinel;13(8):1-7.

https://ctc.westpoint.edu/engineered-pathogens-and-unnatural-biological-weapons-the-future-threat-of-synthetic-biology

[3] 80.000 Hours (2023). What are the most pressing world problems?

https://80000hours.org/problem-profiles/

[4] Niggemeyer Julia (2024). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for pandemic pathogen diagnostics: How it differs from PCR and why it isn’t more widely used . Published on “Effective Altruism Forum”.

https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/Gcoqbn3mphgn5cfF2/loop-mediated-isothermal-amplification-lamp-for-pandemi

[5] Kellner, M.J., Koob, J.G., Gootenberg, J.S. et al. (2019). SHERLOCK: nucleic acid detection with CRISPR nucleases. Nat Protoc 14, 2986–3012.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-019-0210-2

[6] Ashby, Ben et al. (2021). Herd immunity. Current Biology, Volume 31, Issue 4, R174 – R177. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982221000397

[7] World Health Organization (2020). How are vaccines developed?

https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/how-are-vaccines-developed

[8] Krammer, F. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in development. Nature 586, 516–527. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2798-3

[9] Anthony S. Fauci (2021).The story behind COVID-19 vaccines. Science; 372,109-109.DOI:10.1126/science.abi8397.

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abi8397

[10] Witold Więcek (2023) From Warp Speed to 100 Day. Published on “Asterisk Magazine”.

https://asteriskmag.com/issues/04/from-warp-speed-to-100-days

[11] Litvinova VR, Rudometov AP, Karpenko LI, Ilyichev AA. (2023). mRNA Vaccine Platform: mRNA Production and Delivery. Russ J Bioorg Chem.;49(2):220-235. doi: 10.1134/S106816202302015.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1134/S1068162023020152

[12] The adaptive platform trial toolbox: https://covid19trials.eu/en/adaptive-platform-trial-toolbox?

[13] Coccia, M. (2023). COVID-19 Vaccination is not a Sufficient Public Policy to face Crisis Management of next Pandemic Threats. Public Organiz Rev 23, 1353–1367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00661-6

[14] Vaccination contre le Covid en France : au 10 janvier 2022, 28 854 920 doses de rappel ont été réalisées. Published on “sante.gouv.fr/”.

https://sante.gouv.fr/archives/archives-presse/archives-communiques-de-presse/article/vaccination-contre-le-covid-en-france-au-10-janvier-2022-28-854-920-doses-de

[15] Data from Robert Koch Institut on https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_vaccination_in_Germany#Vaccination_by_federal_state

[16] World Health Organization (2022). WHO releases global COVID-19 vaccination strategy update to reach unprotected.

https://www.who.int/news/item/22-07-2022-who-releases-global-covid-19-vaccination-strategy-update-to-reach-unprotected

[17] EU Vaccines Strategy published on commission.europa.eu. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/coronavirus-response/public-health/eu-vaccines-strategy_fr#vaccination-preparedness

[18] Barranco R, Vallega Bernucci Du Tremoul L, Ventura F. (2021). Hospital-Acquired SARS-Cov-2 Infections in Patients: Inevitable Conditions or Medical Malpractice? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 9;18(2):489. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020489

https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/2/489

[19] UNICEF (2020). Teachers should be prioritized for vaccination against COVID-19.

https://www.unicef.org/lac/en/press-releases/teachers-should-be-prioritized-vaccination-against-covid-19

[20] Nick Morrison (2021). These 17 Countries Have Prioritized Teachers For Vaccination. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/nickmorrison/2021/04/02/these-17-countries-have-prioritized-teachers-for-vaccination/

[21] Covid-19 : la vaccination ouverte à tous les adultes dès le 31 mai (2021). Le Figaro. https://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/covid-19-la-france-va-avancer-l-ouverture-de-la-vaccination-pour-tous-les-adultes-20210520

[22] Germany to open up vaccines to all adults from June 7th (2021). The Local. https://www.thelocal.de/20210518/germany-to-open-up-vaccines-to-all-adults-from-june-7th-what-you-need-to-know

[23] Michael Pidwirny & Scott Jones. Trophic Pyramids and Food Webs.

http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/9o.html

[24] Saha S, Chatterjee P, Basu S, Nasipuri M, Plewczynski D. (2019). FunPred 3.0: improved protein function prediction using protein interaction network. PeerJ. 22;7:e6830. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6830. PMID: 31198622; PMCID: PMC6535044.

https://peerj.com/articles/6830/

[25] Barabási, A.-L. (2016). Network science. Cambridge University Press. Online version: https://networksciencebook.com

[26] Caldarelli, Guido (2007) ‘Technological networks: Internet and WWW’, Scale-Free Networks: Complex Webs in Nature and Technology, Oxford Finance Series, online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Jan. 2010).

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199211517.003.0010

[27] Caldarelli, Guido. (2007). ‘Social and cognitive networks’, Scale-Free Networks: Complex Webs in Nature and Technology, Oxford Finance Series (Oxford, 2007; online edn, Oxford Academic, 1 Jan. 2010).

https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199211517.003.0011

[28] Albert, R., Jeong, H. & Barabási, AL. (2000). Error and attack tolerance of complex networks. Nature 406, 378–382.

https://doi.org/10.1038/35019019

[29] Ebel H, Mielsch LI, Bornholdt S. (2002). Scale-free topology of e-mail networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2002 Sep;66(3 Pt 2A):035103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.66.035103. Epub 2002 Sep 30. PMID: 12366171.

https://journals.aps.org/pre/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevE.66.035103

[30] Keeling Matt J and Eames Ken T.D. (2005). Networks and epidemic models. J. R. Soc. Interface.2295–307.

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsif.2005.0051

[31] Yang, C.H., Jung, H. (2020). Topological dynamics of the 2015 South Korea MERS-CoV spread-on-contact networks. Sci Rep 10, 4327.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61133-9

[32] Pavel Skums, Alexander Kirpich, Pelin Icer Baykal, Alex Zelikovsky, Gerardo Chowell (2020). Global transmission network of SARS-CoV-2: from outbreak to pandemic. medRxiv. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.22.20041145

[33] Liljeros, F., Edling, C., Amaral, L. et al. (2001). The web of human sexual contacts. Nature 411, 907–908.

https://doi.org/10.1038/35082140

[34] Fujimoto, K., Kuo, J., Stott, G. et al. (2023). Beyond scale-free networks: integrating multilayer social networks with molecular clusters in the local spread of COVID-19. Sci Rep 13, 21861. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49109-x

[35] Zonta F, Levitt M. (2022). Virus spread on a scale-free network reproduces the Gompertz growth observed in isolated COVID-19 outbreaks. Adv Biol Regul. Dec; 86:100915. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2022.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbior.2022.100915

[36] Adam, D.C., Wu, P., Wong, J.Y. et al. (2020). Clustering and superspreading potential of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Hong Kong. Nat Med 26, 1714–1719.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1092-0

[37] Stein, Richard A. (2011). Super-spreaders in infectious diseases. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 15, Issue 8, e510 – e513.

https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(11)00024-5/fulltext

[38] Wong G, Liu W, Liu Y, Zhou B, Bi Y, Gao GF. (2015). MERS, SARS, and Ebola: The Role of Super-Spreaders in Infectious Disease. Cell Host Microbe. 14;18(4):398-401. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.09.013.

https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1931312815003820

[39] Brainard J, Jones NR, Harrison FCD, Hammer CC, Lake IR. (2023). Super-spreaders of novel coronaviruses that cause SARS, MERS and COVID-19: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol. Jun;82:66-76.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.03.009. Epub 2023 Mar 30. PMID: 37001627; PMCID: PMC10208417.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.03.009

[40] Woolhouse ME, Dye C, Etard JF, Smith T, Charlwood JD, Garnett GP, Hagan P, Hii JL, Ndhlovu PD, Quinnell RJ, Watts CH, Chandiwana SK, Anderson RM. (1997). Heterogeneities in the transmission of infectious agents: implications for the design of control programs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 7;94(1):338-42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.338.

https://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/pleins_textes/pleins_textes_6/b_fdi_45-46/010008253.pdf

[41] Paireau J, Mailles A, Eisenhauer C, de Laval F, Delon F, Bosetti P, Salje H, Pontiès V, Cauchemez S. (2022). Early chains of transmission of COVID-19 in France, January to March 2020. Euro Surveill. 27(6):2001953. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917

https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.6.2001953

[42] Endo, A., Abbott, S., Kucharski, A. J., & Funk, S. (2020). Estimating the overdispersion in COVID-19 transmission using outbreak sizes outside China. Wellcome open research, 5, 67. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15842.3

[43] Coronavirus: France’s first known case ‘was in December’ (2020). BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-52526554

[44] Dennis Normile (2013),The Metropole, Superspreaders, and Other Mysteries.Science339,1272-1273.DOI:10.1126/science.339.6125.1272.

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.339.6125.1272

[45] Hirschberg, M. (2012). Living with Chronic Illness: an Investigation of its Impact on Social Participation, Reinvention: a Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 5, Issue 1.

https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/20/6/4940

[46] Marcum, C. S. (2013). Age Differences in Daily Social Activities. Research on Aging, 35(5), 612-640.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027512453468

[47] Nunner, H., van de Rijt, A. & Buskens, V. (2022). Prioritizing high-contact occupations raises effectiveness of vaccination campaigns. Sci Rep 12, 737.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04428-9

[48] Rocha Filho TM, Mendes JFF, Murari TB, Nascimento Filho AS, Cordeiro AJA, Ramalho WM, et al. (2022). Optimization of COVID-19 vaccination and the role of individuals with a high number of contacts: A model based approach. PLoS ONE 17(3): e0262433.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0262433

[49] Pastor-Satorras, R., & Vespignani, A. (2001). Immunization of complex networks. Physical review. E, Statistical, nonlinear, and soft matter physics, 65 3 Pt 2A, 036104. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.65.036104

[50] Brainard J, Jones NR, Harrison FCD, Hammer CC, Lake IR. (2023). Super-spreaders of novel coronaviruses that cause SARS, MERS and COVID-19: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol. 82:66-76.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2023.03.009.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1047279723000583?via%3Dihub

[51] Kretzschmar, Mirjam E et al. (2020) Impact of delays on effectiveness of contact tracing strategies for COVID-19: a modelling study. The Lancet Public Health, Volume 5, Issue 8, e452 – e459.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(20)30157-2/fulltext

[52] Read AF, Baigent SJ, Powers C, Kgosana LB, Blackwell L, Smith LP, et al. (2015) Imperfect Vaccination Can Enhance the Transmission of Highly Virulent Pathogens. PLoS Biol 13(7): e1002198.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002198

[53] M. Kodialam, T. Nandagopal and W. C. Lau, (2007). Anonymous Tracking Using RFID Tags. IEEE INFOCOM 2007 – 26th IEEE International Conference on Computer Communications, Anchorage, AK, USA, pp. 1217-1225, doi: 10.1109/INFCOM.2007.145.

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/4215727

[54] Jen Kwon (2020). A new coronavirus cluster linked to Seoul nightclubs is fueling homophobia. CBS News.

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/south-korea-coronavirus-cluster-linked-to-seoul-nightclubs-fueling-homophobia-fears-gay-men/

[55] Scott L. Feld (1991). Why Your Friends Have More Friends Than You Do. American Journal of Sociology 96:6, 1464-1477

https://pdodds.w3.uvm.edu/teaching/courses/2009-08UVM-300/docs/others/everything/feld1991a.pdf

[56] The Friendship Paradox And You: https://www.alexirpan.com/2017/09/13/friendship-paradox.html

[57] Cohen, R., Havlin, S., & Ben-Avraham, D. (2003). Efficient immunization strategies for computer networks and populations. Physical review letters, 91(24), 247901. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.247901

[58] Eugenia Tognotti (2021). When In Doubt: Vaccine Hesitancy in Europe. Institut Montaigne.

https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/when-doubt-vaccine-hesitancy-europe

[59] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trolley_problem

Credit for featured picture: freepik